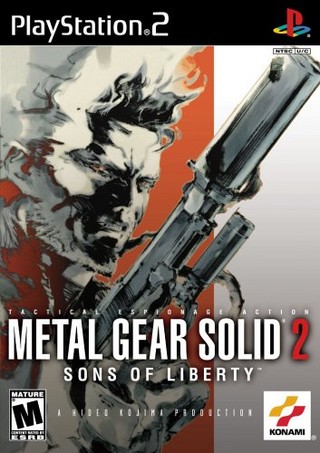

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty ( メ タ タ ル ギ ア ア ソ リ ッ ド サ 2) . The game is a direct continuation of the successful Metal Gear Solid and can chronologically be considered the seventh game in the Metal Gear series , as well as the fourth game created with the participation of Kojima. Subsequently, an expanded edition of the game was created called Metal Gear Solid 2: Substance . In 2004, the Metal Gear Solid 3 prequel followed : Snake Eater , and in 2008, the Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots game, a continuation of Sons of Liberty.

Read more...

O'Shea, John

John Francis O'Shea [4] ( Eng. John Francis O'Shea , Irl. Seán Sé , MFA / oʊ eɪ / [5] ; born April 30, 1981 in Waterford , Ireland ) - a former Irish footballer known for on performances for the English clubs " Manchester United " and " Sunderland ". Universal player: could act on the position of the central, flank defender and defensive midfielder . Occasionally appeared on the position of the central striker and goalkeeper. He is the third player in the number of matches for the Ireland national team (118 games).

Read more...

Today, Tomorrow And Forever

Today, Tomorrow And Forever - a box set of American musician Elvis Presley , released on the eve of the anniversary of " BMG " in June 2002 under the label " RCA Records ". The box set includes 4 CDs , which contain 100 rare, previously unreleased recordings by the musician , as well as alternative versions of songs made from 1954 to 1976.

Read more...

All Articles